America Exported Measles to Mexico. Now What?

The U.S. is Fumbling Our Measles Response.

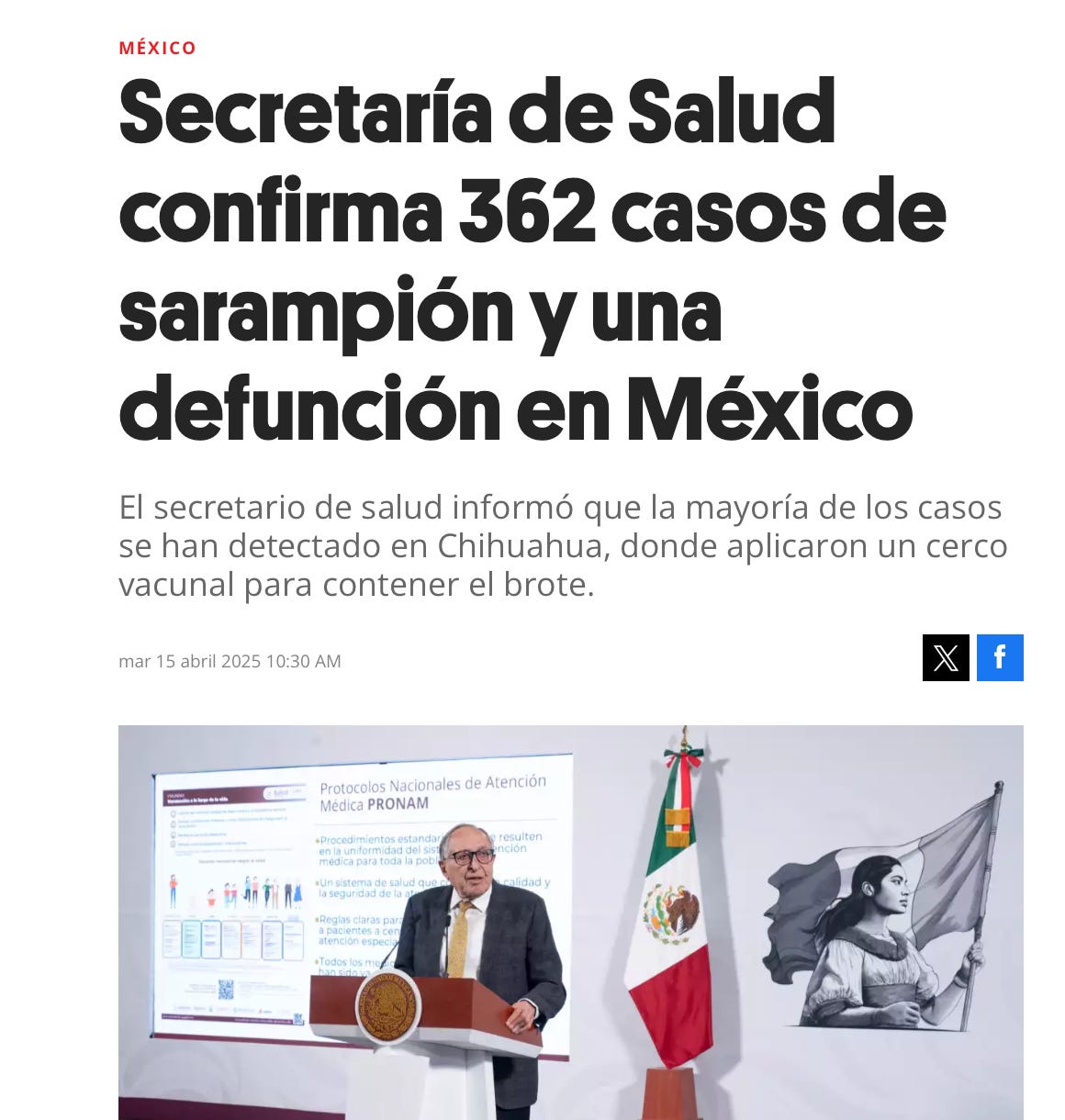

Today, Mexico has hundreds of cases of measles - or "sarampión" in Spanish - connected with exposure to visitors from Texas.

“Keeping up with measles outbreaks” was never on my list of reasons to practice my Spanish reading skills.

Yet here we are….

An ongoing measles outbreak in Chihuahua, Mexico, began in February 2025. The first confirmed case was reported on February 20, 2025.

As of April 19, 2025, there are over 417 cases in 7 of Mexico’s 31 states.

The vast majority are in Chihuahua, a Mexican state that borders Texas. These cases include one death and five hospitalizations from serious complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis, and liver damage.

Most of the Chihuahua cases are clustered in rural Mennonite communities near Cuauhtémoc.

Mexico measles outbreak is growing fast, already far surpassing its 2020 outbreak which peaked at 196 cases.

Viral Clues

How do we know that the major measles outbreak in Mexico originated in Texas?

By studying the genotype of an a virus in a measles outbreak, we can understand how a virus travels and places new populations at risk. Genotyping is crucial for understanding the epidemiology of measles outbreaks, identifying the source of outbreaks, and guiding public health interventions.

The dominant variant in the Texas outbreak is Genotype D8 - which is what’s also seen in the Chihuahua outbreak. Texas submitted 92 identical DNA sequences of genotype D8. Ten sequences from New Mexico and one from Kansas matched those from Texas. Additionally, Texas reported three genotype D8 sequences with single nucleotide substitutions. 19 genotype D8 sequences have been reported from the affected states.

Measles: An American Export

The outbreak in Chihuahua is directly linked to the outbreak in Texas.

Mexico’s Health Secretary is INSISTING people get vaccinated, and urging Mexican citizens to avoid nonessential travel to Texas, citing the U.S. outbreak as a serious risk.

“However, we must insist that people get vaccinated, especially now that the holiday season is approaching, when there is greater movement of people, including those traveling to, for example, the United States, where there are many more measles cases than we have here.” - David Kershenobich, President of the General Health Council and Secretary of Health

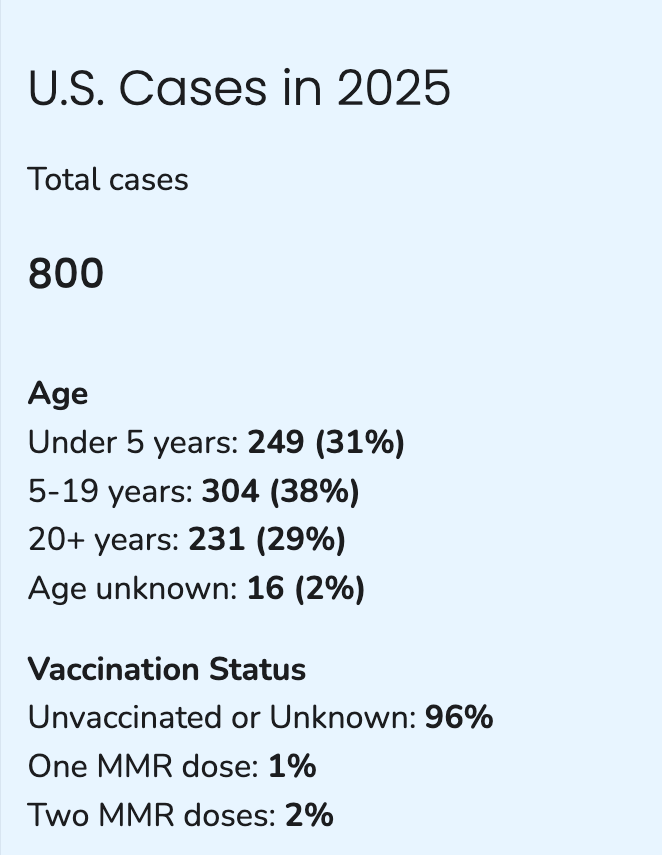

Kershenobich is correct. There’s a lot more measles in the United States right now. Updated numbers from the CDC this week show we have reached 800 confirmed cases in 24 states. We know that this is an underestimation of cases, with actual cases likely in the thousands.

The Gaines Texas outbreak began in January and has continued to spread, largely fueled by low vaccination rates and the delayed and uncoordinated response from public health officials.

Both the Texas and the Chihuahua outbreaks are centered in rural Mennonite farming communities, where vaccine uptake has been especially low.

Immigrants are Blamed - Again

We don’t yet know how the Gaines, Texas outbreak started. We don’t know how the virus entered a rural Mennonite community.

Despite the evidence that the Texas outbreak has spread to Mexico (not the other way around), political figures and pundits in the U.S. have quickly pointed fingers at immigrants and asylum seekers.

Pennsylvania congressman Rep. Ryan Mackenzie told Jake Tapper: “First of all, many of these instances that are coming into our country are from illegal immigrants who have crossed the border with no checks, no actual health records, and they are bringing these diseases into our country.”

Rep. Mackenzie’s comments drew immediate backlash from health experts and advocates, who noted the dangerous precedent of scapegoating during outbreaks.

This narrative isn’t new. Throughout its history, the U.S. has often responded to public health threats by targeting immigrants and marginalized communities. The fear of “imported disease” has frequently been used to justify exclusionary immigration policies, shaped by racism, ableism, and economic bias.

Blaming migrants for outbreaks - particularly one that originated in the U.S. - is not only inaccurate, it perpetuates a long-standing pattern of prejudice masquerading as public health policy.

Amesh A. Adalja and Agustina Vergara Cid warned of this risk in their STAT News op-ed:

Paradoxically, the administration whose health secretary wants to institute a “pause” on infectious disease research and expresses doubt regarding the germ theory of disease is now going to invoke infectious diseases as a threat.

In order to invoke Title 42, the CDC must determine that migrants at the border pose a public health risk — that they bring in tuberculosis or other significant communicable diseases at a rate that would make it cumbersome for U.S. public health officials to identify or contain the threat.

The Viral Travel Cycle

Measles is wildly infectious. When outbreaks are left unprevented and unchecked, the virus travels easily.

A baby in Denver, Colorado recently contracted measles after visiting Chihuahua. The infection was linked to the ongoing outbreak in the region. At under one year, the child was too young to be vaccinated.

From Gaines, Texas to Chihuahua and back to the US via Denver, Colorado.

What we’re seeing is a clear example of cross-border disease transmission, driven not by migration but by gaps in public health infrastructure and vaccine coverage - on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Global Measles Surveillance On The Brink

As the U.S. struggles to respond domestically, global systems are faltering due to U.S. funding cuts. The Global Measles and Rubella Laboratory Network - a vital tool for outbreak detection and response - is facing potential collapse after Trump withdrew the US from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC withdrew its funding.

This choice undermines the global ability to track infectious disease outbreaks and take appropriate public health actions.

For 25 years, the network has operated across 150 countries, identifying outbreaks early and coordinating international responses. Its loss would leave the global community - and the US - significantly less prepared to respond to emerging threats - not just for measles, but also for future pandemics.

Mexico’s Proactive Public Health Response is Far Superior to RFK Jr’s Messaging

The biggest difference in today’s outbreak is that Mexico’s public health leadership is presenting strong, evidence-based advice, while RFK Jr continues to suggest vaccination while undermining its effectiveness.

In contrast to the U.S. response, Mexico’s health leadership has taken swift and transparent action.

The Secretary of Health is pushing vaccination for all Mexicans and discouraging travel to the United States. The country has already successfully vaccinated 700,000 people since the outbreak began.

Meanwhile, Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is sending mixed messages about vaccines and measles prevention. While he surprised public health advocates - and pissed off MAHA movement - by encouraging vaccination, he’s also continued to undermine vaccination and promote ineffective treatments, like vitamin A.

Beyond bad advice on measles management, the director of Health and Human Services praised anti-vaccine physician Ben Edwards for practicing while actively infected with measles. In the U.S., we are in the public health bad place.

The United States continues to fall below the 95% MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccination rate needed for herd immunity. The result: school-based outbreaks, community spread, and rising hospitalization rates.

RFK Jr has long promoted discredited views on vaccines. Now, he is supposed to be leading the country’s response to a vaccine-preventable outbreak. His influence risks undermining public trust in immunization during a moment when confidence and clarity are urgently needed.

Misplaced Blame Distracts from Real Solutions

The real drivers of this outbreak are preventable: underfunded health systems, declining vaccination rates, rampant misinformation and disinformation, and political interference in public health messaging.

Redirecting blame toward migrants obscures these root causes. It also reinforces stigmatizing narratives that have been used for over a century to police borders and punish marginalized communities under the guise of disease control.

We need increased vaccination coverage. We need strong, unified public health messaging - especially from RFK Jr. We need functioning global surveillance systems. And we need leaders who will prioritize public safety over political expediency and anti-vaccine ideology.

This outbreak isn’t about migration. It’s about accountability.