Patient Autonomy Crushed in Major Supreme Court Ruling

Freedom lost for Medicaid patients under Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic

This week, the Supreme Court landed another major blow to patient autonomy in America. Less than a week after the court authorized discrimination against transgender patients’ access to medical care, the court has decided to throw a wrench into Medicaid regulations meant to protect patients’ access to high-quality care.

In this essay, I’ll break down Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, helping you understand the Medicaid regulations at issue and failed past attempts by anti-abortion states to defund Planned Parenthood, Medina’s impact. I’ll contextualize it in South Carolina’s abysmal maternal and infant health statistics, and call out the implications for patient autonomy.

A Blow to Patient Autonomy

A win for the conservative anti-autonomy movement, Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic has stripped Medicaid recipients of the ability to sue when the state denies them access to qualified providers.

The court was asked, “Does the Medicaid Act’s ‘any qualified provider’ provision unambiguously confer a private right upon a Medicaid beneficiary to choose a specific provider?” A private right of action essentially grants individuals the power to seek legal recourse and remedies for harm they've experienced due to a breach of certain legal obligations.

In the 6-3 decision down predictable ideological lines, Justice Neil Gorsuch and the other five conservative justices decided no: a person does not have the right to sue the state for denying access to Planned Parenthood as a provider. (Thomas wrote his own dissenting opinion.) Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson dissented from the court’s ruling, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

The decision removes a key provision that protects patients from bad-faith limitations placed on Medicaid beneficiaries. This may be one of the most consequential healthcare decisions, not just of this SCOTUS season, but for years to come. This decision places low-income Americans at an extremely worsened risk of poor care under the direction of hostile states to social benefits.

Medicaid, the “Any Qualified Provider” Rule, and Patient Choice

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Social Security Amendments of 1965, commonly referred to as the Medicare and Medicaid Act, into law. It established Medicare, a health insurance program for older people, and Medicaid, a health insurance program for low-income Americans and people with disabilities. The program is administered by the states. Medicaid, in particular, was made for individuals and families “whose income and resources are insufficient to meet the costs of necessary medical services.”1

When providing federal funding, the government imposes conditions for participation in the program. These over 80 conditions have evolved since the beginning of Medicare and Medicaid. To provide and bill for Medicaid-eligible services, hospitals and clinics must comply with these restrictions. This allows medical care for the least well off in American society to be provided by clinicians and organizations with the skillset and resources to provide care.

One of the long-standing requirements for participating in Medicaid is that patients have the right to choose their provider, so long as that person is qualified to provide that care. The Social Security Act says Medicaid beneficiaries generally have the right to obtain medical services “from any institution, agency, community pharmacy, or person, qualified to perform the service or services required . . . who undertakes to provide . . . such services.” The “any willing provider” or “free choice of provider” provision, until Medina, required state plans to allow patients to seek Medicaid services from “any institution, agency, pharmacy, person, or organization that is (i) qualified to furnish services and (ii) willing to furnish them to that particular beneficiary.2

Abortion Access and the Targeting of Planned Parenthood

Since shortly after the legalization of federal abortion access under Roe, federal regulations have restricted coverage for abortion services. The Hyde Amendment, introduced in 1976 and enacted in 1980, restricts the use of federal funds to pay for abortions, with exceptions only for cases of rape, incest, or when the mother's life is in danger. Shortly after taking office, Trump released an executive order reinforcing Hyde.

Defunding Planned Parenthood has been a right-wing/conservative aim for decades. In the wake of a sensationally edited video created by anti-abortion advocates in 2015, six states tried to bar Planned Parenthood from participating in their Medicaid programs. Under Hyde, the organization was already barred from using federal money except for an extremely limited number of abortions, but states argued these clinics did not meet Medicaid standards, claiming that Planned Parenthood was engaging in illegal activity and therefore unqualified to deliver care. Medicaid regulations do not define who is qualified to deliver care, leaving that up to the states.

In response, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a letter clarifying that states could not use a biased approach to target certain healthcare providers (abortion providers) and that they must comply with patients’ freedom of choice. The government states that a qualified provider must be based on their “capability of performing the needed medical services in a professionally competent, safe, legal, and ethical manner.”

States claimed this prevented them from regulating the practice of medicine. At the time, CMS called them out on this nonsense. The requirement to ensure patient choice of provider does not prevent the states from regulating the practice of healthcare appropriately. States still need to establish and enforce provider standards and take action against providers who are genuinely unfit for practice or who do not appropriately bill for services (engage in Medicare fraud). Medicare beneficiaries deserve high-quality care. Being low-income should never be used as an excuse for inadequate care from charlatans or criminals.

In his effort to appease anti-abortion Christian conservatives, the letter was rescinded in 2018 under the first Trump administration. Several federal lawsuits followed, questioning whether patients have a private right of action against states that excluded qualified providers. SCOTUS declined to hear one of these cases, leaving lower court rulings in effect. The Medicaid regulations remained in effect and open for interpretation, leading to the Medina case.

What the Supreme Court Decided in Medina v. Planned Parenthood

Previous attacks on Planned Parenthood focused on whether Planned Parenthood was unqualified under Medicaid because the clinics also offer abortions. In Medina, instead of going after providers as unqualified, the case attacked patients’ right to choose a qualified healthcare provider at all.

In 2018, citing state law prohibiting public funds for abortion, South Carolina determined Planned Parenthood could no longer participate in the State’s Medicaid program. Julie Edwards, a Medicaid recipient, wanted her gynecologic care to be provided at Planned Parenthood.

Edwards and Planned Parenthood sued the state3, claiming the exclusion of Planned Parenthood violated the any-qualified-provider provision. They brought a class action suit under the § 1983 Civil Rights Act of 1871 “to vindicate rights secured by the federal Medicaid statutes.” Applying for relief under §1983 generally requires a violation of rights protected by the Constitution or created by federal statute, caused by conduct of a ‘person’ acting under color of state law.

South Carolina was represented by John Bursch, a lawyer with the far-right Christian legal advocacy and training group Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF).4 The group, responsible for ending the federal right to abortion, enabling businesses to discriminate against gay people, and allowing states to ban gender affirming care for minors, is on a crusade to end abortion and LGBTQ civil rights in every nook and cranny of America.

Planned Parenthood provides a host of preventative healthcare services beyond abortion and has been able to offer those services to Medicaid patients. The organization provides family planning care, contraception services, vaccinations, sexual education, testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, initial prenatal care (and referrals for ongoing care), as well as screening for cervical and breast cancer. As a Title X recipient (since 2022), Planned Parenthood of South Carolina provides services that are voluntary, confidential, and provided regardless of ability to pay.

In their case, South Carolina conceded that Planned Parenthood could receive Medicaid funding if it shut down the provision of abortion. This means the State aims to remove specific qualified doctors who are willing to provide a wide range of services to patients, only because the State disagrees with access to a specific safe, effective, and legal healthcare service (abortion).

People who receive care via Medicaid already face significant barriers to care and limited choices – not all providers accept Medicaid patients. Because Medicaid reimbursements are significantly lower than those for private insurance, there are already too few clinicians who accept Medicaid.

“Today’s Supreme Court decision is yet another attack on reproductive health care in this country, but the harm it will cause extends well beyond reproductive health care, as patients will miss opportunities for vaccination, earlier diagnoses of treatable cancers, screenings for curable sexually transmitted infections, and prenatal and postpartum care. By making it harder for people to get the care they need from health care providers that they choose and trust, this decision will worsen outcomes for our patients and make our communities sicker.”

– ACOG Statement on the Supreme Court Decision in Medina v. Planned Parenthood, June 26, 2025

By allowing the state to bar Planned Parenthood from providing Medicare services via qualified medical providers solely because the clinic also provides abortions, the state will significantly decrease care options for its own, already underserved population.

South Carolina’s Poor Health Outcomes for Moms & Kids

South Carolina remains one of only ten states to have consistently refused to expand Medicaid access under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This year, that may change, as the legislature introduced a bill in January to allow South Carolinians with incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty line to use the service. (Given the $1 trillion cuts to Medicaid proposed in the No Good, Very Bad Bill being negotiated in the Senate this week, South Carolina may have come to the party far too late to help its people.)

Poor health outcomes for mothers and babies are significantly related to poverty and other social determinants of health. Across South Carolina’s 46 counties, the estimated poverty rate ranges from 8.3 to 36.7%, with an overall median rate of 14.0%. The estimated poverty rate for children aged 5 to 17 ranges from 10.0 to 49.7%, with a median rate of 18.4%. According to Children’s Health Data, more than 40% of children in the state rely on the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)5, and 36% of families with children in the state report being unable to afford nutritious food or to eat at all. For South Carolinians who are able to work, many rely on Medicaid because workers are paid so poorly and in jobs that do not offer private health insurance.6

South Carolina has 1.2 million women of reproductive age and a very high Maternal Vulnerability Index (MVI). 16.1% of South Carolina moms receive inadequate prenatal care. Five counties in the state are maternity care deserts, without access to any hospitals, birthing centers, or obstetricians, and 12 counties have low access to such care.

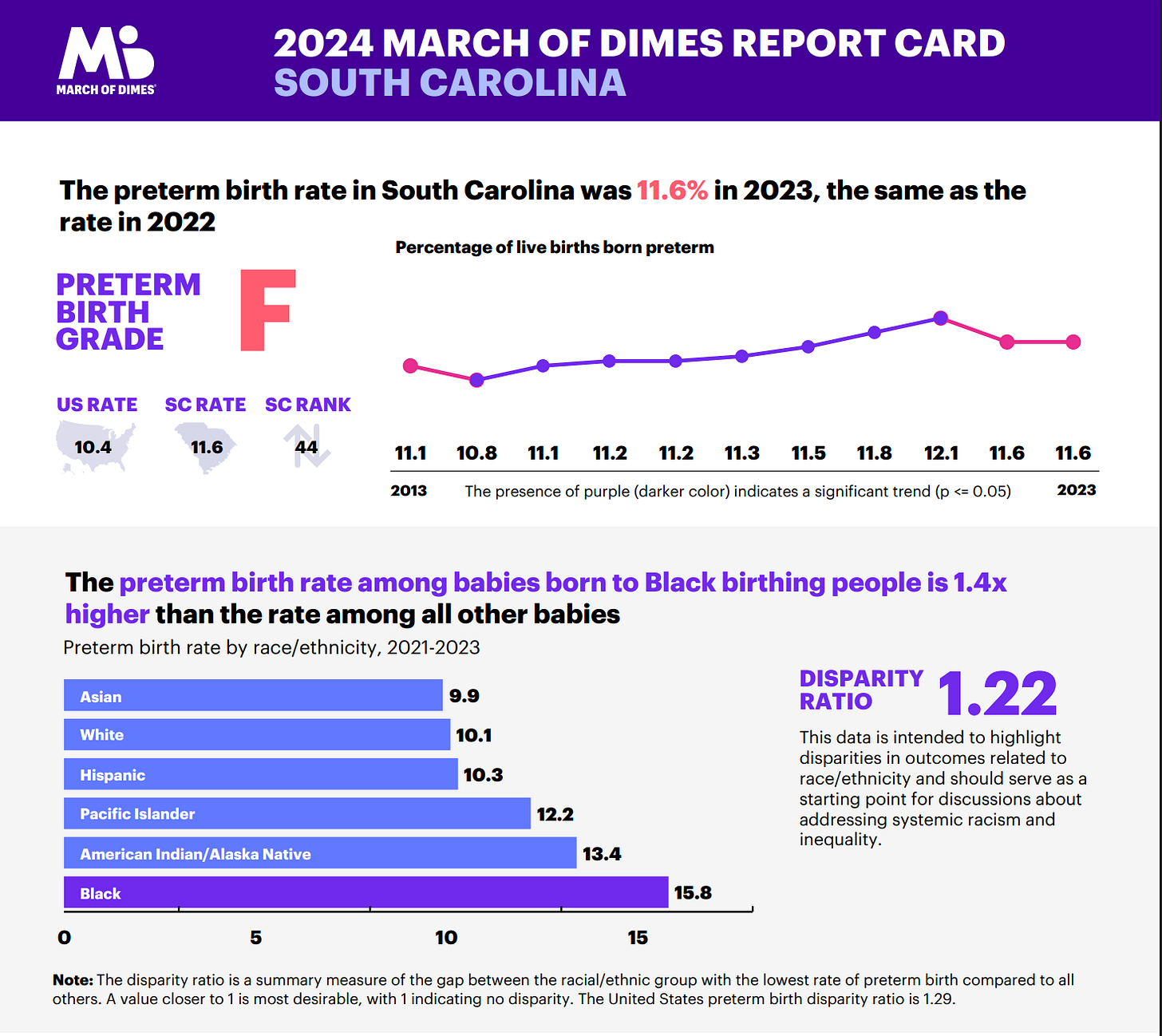

The maternal death rate in the state is 32.3 deaths per 100k births, significantly higher than the already poor national average of 23.2%. March of Dimes scores each US state based on its preterm birth outcomes. They rank South Carolina 44th out of 52 districts and grade it F for a preterm birth rate. The infant mortality rate is also higher than the national average at 6.8% per 1000 live births. There are significant racial disparities in maternal and infant outcomes.

In an analysis of US states’ abortion policies compared to maternal health outcomes, states with more restrictive abortion policies also tend to have higher rates of maternal mortality. Additionally, states that restrict state Medicaid funding for abortion are associated with a 29% higher total maternal mortality.

South Carolina already drastically limits abortion access, banning it beyond 6 weeks, imposing mandatory waiting periods, and medically unnecessary ultrasounds. The State bans the use of telehealth to obtain medication abortion pills, and only physicians can provide abortion care (excluding other qualified and trained professionals, such as CNMs, NPs, and PAs), among many other barriers. South Carolina also imposes targeted restrictions on abortion providers (TRAP laws), requiring unnecessary standards such as corridors to be a certain width and that providers have admitting privileges at a local hospital.

Planned Parenthood has been plugging holes in the US safety net for decades. The organization’s health centers are major sites of care, especially in areas where other options are limited or unavailable. Seventy-six percent of centers are located in rural, medically underserved or areas with shortages of healthcare professionals. 53% of patients served rely on Medicaid or the Title X Family Planning Program. Two out of three patients reported that publicly funded health centers, like Planned Parenthood health centers, were their primary source of medical care. In a survey of patients from two Planned Parenthood health centers in Kentucky and Louisiana (states likely to follow South Carolina in excluding PP from Medicaid), 60% did not have a regular source of health care besides Planned Parenthood.

Autonomy, But Only for the Privileged

Autonomy is one of the four oft-cited pillars of bioethics. Autonomy – the ability to make an uncoerced and free choice about one’s healthcare – is an especially valued bioethical principle in American culture. In many ways, autonomy dominates American bioethical discourse.

Medicaid should include policies that ensure patient autonomy. The decision in Medina v. Planned Parenthood assaults patient autonomy on multiple fronts.

The state leaves patients who would otherwise use Planned Parenthood with fewer options in an already limited pool of willing providers.

For some patients, this will mean no access to any qualified provider at all. You can’t make autonomous choices about health when you have severely limited or no access to alternatives.

This gives states the ability to regulate patient access to numerous Medicaid services in a discriminatory fashion.

Patients will no longer be able to sue for access choice. Given the lack of private action available to patients, they have one less mechanism to compel states to follow federal regulations.

Medina’s impacts on Medicaid access far beyond reproductive healthcare, making many of the federal regulations around the safety net essentially unenforceable. This means that when the federal government does not step in to enforce patient access to a “free choice of provider” – not just for reproductive health but for any healthcare - patients also do not have access to sue for violations of their access.

This decision dismisses the dignity of low-income Americans, in particular, of low-income women of color. It further compounds the significant burdens faced by low-income Americans.

You can have autonomy, but only if you’re wealthy.

You can have autonomy, but only if can afford to pay for access to choice outside of Medicaid.

You have autonomy, but not for reproductive health.

These assaults on patient autonomy further harm other critical principles in bioethics – beneficence (offering what benefits patients), non-maleficence (preventing patient harm), and justice (ensuring equitable access to care). Certainly, the ethics of care are conspicuously absent in this case.

When patients cannot choose any qualified provider, the state is then free to drastically limit the providers available to choose from. The 2016 CMS letter highlighted discriminatory practices against qualified providers. Medina codifies this ability. States may now, with impunity, bar patients from seeking care in clinics that provide services the state doesn’t like, despite those services being legal for patients to obtain. More and more providers will now fall into a “willing but unable” category when it comes to reproductive healthcare services.

The Anti-Autonomy Court

The anti-abortion movement is an anti-autonomy movement. They have successfully stacked the Supreme Court in their favor. The court’s conservative majority appears dead set against safeguarding patients’ access to evidence-based healthcare. The court burdens Americans by refusing to uphold medical decision-making authority for those most impacted (patients) and qualified (healthcare workers).

Where will it end? South Carolina has now successfully further restricted access to Planned Parenthood’s services via Medicaid. Other abortion restrictive states will follow. Will the states now also use this ruling to strong-arm larger hospital systems to limit choices for their Medicare beneficiaries? Will any hospital that provides comprehensive care be at risk of losing the ability to care for Medicaid patients? Will there be anyone left to care for them at all?

42 CFR § 1396-1 - Appropriations

42 CFR § 431.51(b)(1) - Free Chocie of Providers

Eunice Medina is the interim Director of the South Carolina Health and Human Services

As far as I can tell, the ADF’s goals are to oppress the freedom of non-Christians at every turn.

CHIP is a Medicaid program

South Carolina has no state-specific minimum wage, so folks earn the federal minimum of $7.25 per hour.

It appears that Stephen Miller's Aryan Supremacy statement of "If I was President the US would have only 100 million people and they'd all look like me." is being enacted by denying appropriate (my def: best quality based on patient need) healthcare to women who need Medicare/Medicaid ensuring that the infant and maternal death rates of "undesirables" (Hitler's name for Jews, Romani, People of color, and LGBQi people) skyrockets.